A brief history of St. Patrick's Day in America

Ian LamontSt. Patrick’s Day takes place on Sunday. In the past, I’ve lamented its transformation from what was once a quiet religious observation (commemorating both Saint Patrick's death and the arrival of Christianity in Ireland) into an excuse to get blotto. But the story goes deeper than that.

Irish have been coming to North America since the 1600s, but initial numbers were small. That changed with The Great Famine (1846-1851). The gentry and the press decried the influx of destitute Catholic Irish immigrants arriving in East Coast ports, along with Chinese immigrants arriving on the West Coast.

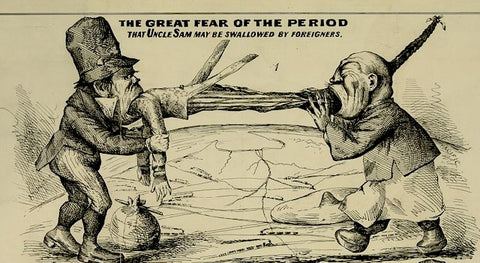

In this 1860 drawing, racist Irish and Chinese caricatures are shown devouring Uncle Sam:

In the decades that followed, St. Patrick’s Day would become a rallying point, celebrating the pride many Irish immigrants and their children felt as Americans, and the continued concern for Ireland under British rule.

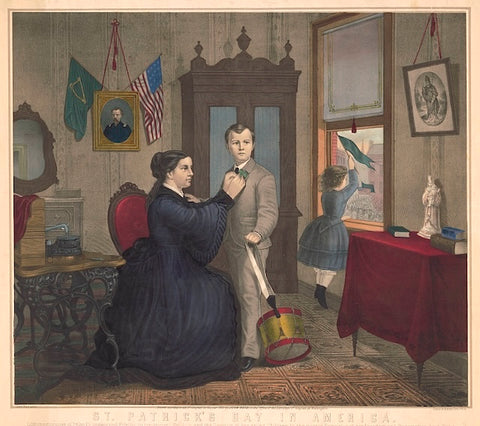

According to the Library of Congress, the following 1872 print "… shows a mother pinning clover on her son's suit lapel, on the right is a young girl standing at an open window waving a banner 'God save Ireland.'"

But this experience is also very American. The boy is getting ready to participate in a parade. There are flags on the wall representing the U.S. and Ireland, along with a portrait of President Ulysses S. Grant. These immigrant families wanted to be accepted as Americans, while honoring their heritage.

1927 film banned after offending Irish Americans

Popular media continued to portray Irish Americans in a negative light. The New York Times describes “The Callahans and the Murphys,” a silent 1927 MGM comedy that was so offensive it was pulled from circulation:

The plot centered on two tenement Irish families in a place called Goat Alley, where, a title card explained, “a courteous gentleman always takes off his hat before striking a lady.” … There are fleas and chamber pots and thumbed noses and a St. Patrick’s Day picnic that — hold on to your shillelagh! — devolves into a drunken brawl.

The New York Times article notes that the country’s Irish Catholics “already felt under attack by a resurgent and powerful Ku Klux Klan that mocked their faith and questioned their patriotism.”

Indeed, the stereotype of “unpatriotic” Catholics would linger until 1960, when the election of John F. Kennedy finally put it to rest.

As Americans from many backgrounds know, ethnic stereotypes are damaging, and reflect some of the darker undercurrents of our society.

However, if enough people open their eyes and raise their voices, attitudes can shift, not just for Irish Americans, but for the many other groups of people who make up our great nation.

St. Patrick's Day is an opportunity to celebrate Irish heritage, whether it's through song or feasting or research into Irish immigrant ancestors. Happy St. Patrick's Day to those who observe.