The surprising genealogy math about our ancestors in the year 1000 C.E.

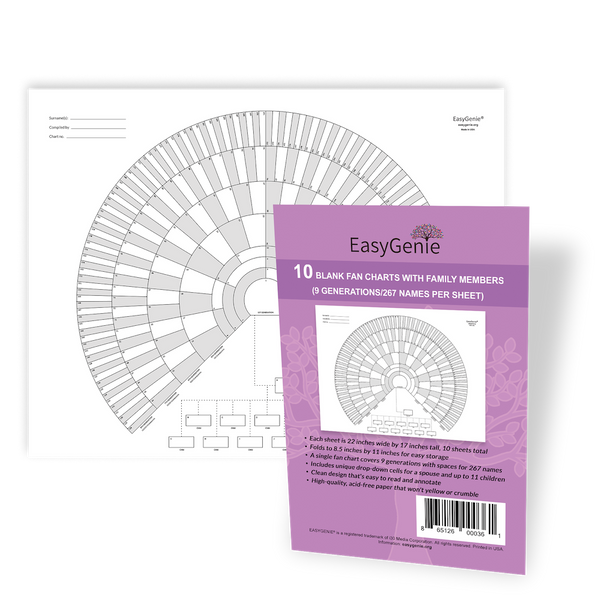

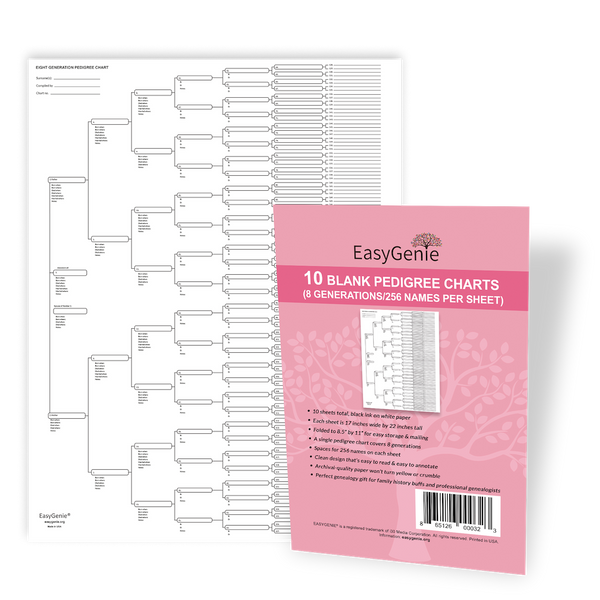

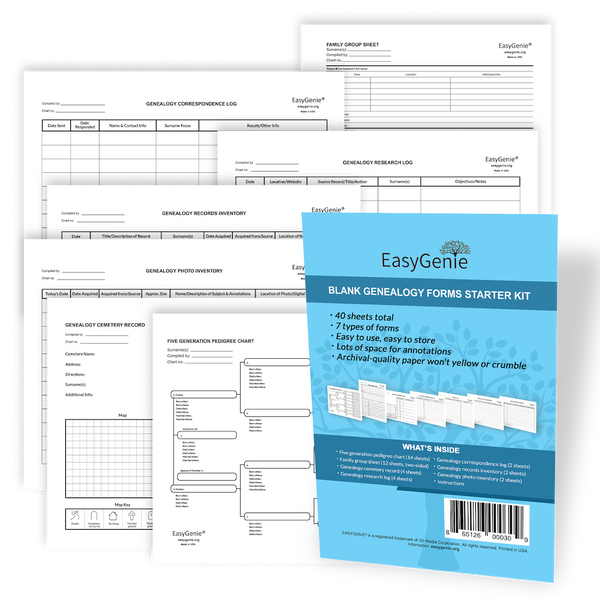

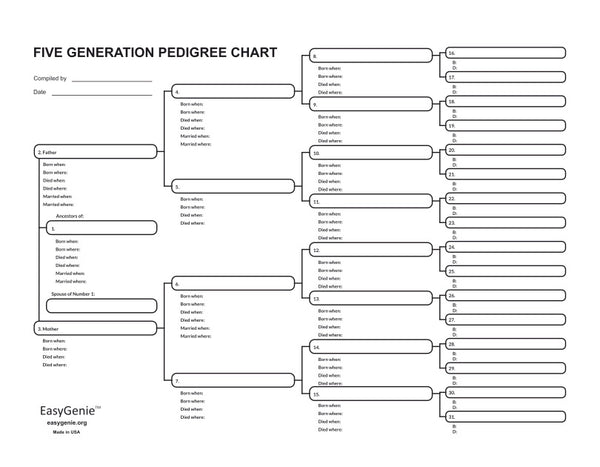

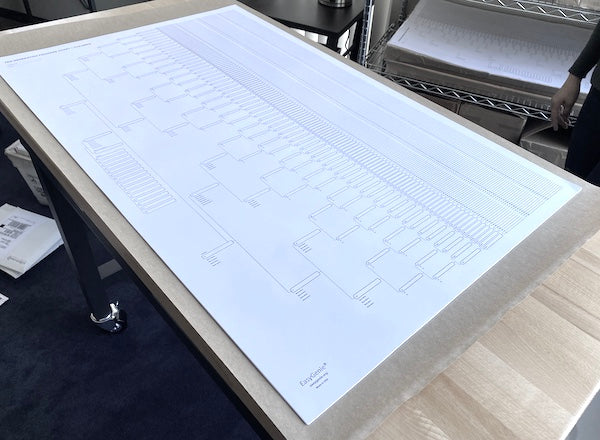

Ian LamontLet's talk about genealogy math, starting with a question customers sometimes pose: Why doesn’t EasyGenie sell charts that are bigger than the 22” by 36” 10-generation pedigree chart shown above? Here’s an example:

“I have 24 generations, I would like to be able to view on one large sheet. Do not want printing on back. Folding or rolling chart is fine, but would like one large sheet where all 24 generations are visible. Is it possible to generate such a form and not with the super tiny print when you get to upper generations.”

Creating such a paper chart is not possible, based on the simple fact that going back one generation doubles the number of ancestors, with a corresponding increase in the size of paper required.

A human has two biological parents, four grandparents, eight great-grandparents, and so on. Ten generations back (to the early 1700s on most lines) a person has 2^10 ancestors, or 1,024 people. Each one of those ancestors also has 1,024 ancestors 10 generations further back (to the early 1400s) or over a million people at 20 generations. I hope you are beginning to understand the challenge of making paper charts that big!

Genealogy math has other implications. A white paper published by FamilyTreeDNA used an example of a Swedish man with 8.5 billion genealogical ancestors (2^33) living in the year 1000 C.E. "Genealogical ancestors" does not mean actual ancestors, as there weren't even one billion living humans alive at that time, meaning many ancestors will appear multiple times across various branches. The white paper notes:

“In the year 1000 C.E., Europe only had a population of ~50 million. Some simple math shows that everyone who was alive in Europe around the year 1000 C.E. is an ancestor of everyone in Europe today, or of no one. Therefore, the Swedish man has the same set of ancestors as a man whose family is 100% Iberian.”

Think about that for a moment. If you have a single European ancestor, you are genealogically descended from every European from the year 1000 who has living descendants now. That includes a Polish fisherman living in Gdańsk to an Anglo-Saxon scribe from London to Muniadona of Castile, the wife of King Sancho III of Pamplona.

The same math applies to other distinct global populations. Every living person with Native American ancestry shares the same Amerindian ancestors who were alive one thousand years prior who have living descendants now. That would include Mississippian people who built the Cahokia mounds, the Xochimilca of central Mexico, and members of Thule tribes living above the Arctic Circle.

You may wonder, how come a modern Inuit looks different from, say, a Navajo member, even though they have the same ancestors from 1,000 years ago? Or a woman from Stockholm will likely look much different than someone from Madrid? Quoting the FamilyTreeDNA whitepaper:

“The Swede and Iberian may share millions of genealogical ties. However, the Swede has perhaps 1,000 ties to a Scandinavian ancestor, and the Iberian man has perhaps only 10 ties to that same Scandinavian ancestor. Thanks to the randomness of genetic recombination, the Swede is 100x more likely to inherit Scandinavian DNA than Iberian DNA.”

There’s another interesting fact that skews our genealogy math: Europe and North America and all of the other continents were not cages. Travel was possible between these areas. This is clear from centuries-old accounts of Marco Polo reaching Beijing, Chinese Admiral Zheng He sailing to East Africa, or the Moroccan-born Ibn Battuta travelling to what is now Russia, India, and Indonesia.

There is evidence for other intercontinental voyages. Viking sagas described settlements in Greenland and Newfoundland 1,000 years ago, which is backed up by archaeological findings. For millennia, intrepid Polynesia boat-builders spread across the Pacific, reaching the edge of the Americas.

Did these early intercontinental encounters lead to children? Some did. A few of these offspring may have even hundreds of millions of descendants who are alive today.

Bottom line: the genealogy math shows we are a lot more connected than we may assume.