Thoughts on handling errors in genealogy

Ian LamontI have an apology to make. In a recent genealogy newsletter, I included the following blurb:

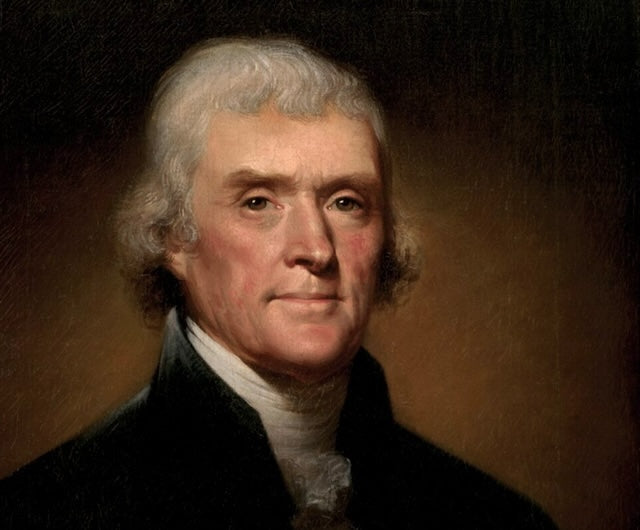

It has been described as “the Harry Potter of the 18th century”, but this was no children’s book and it attracted the attention of some of the world’s greatest names. According to Jefferson’s Literary Commonplace Book, the second US President even wanted to learn Gaelic so he could read the work in its original language.

As some readers pointed out, Thomas Jefferson was the third U.S. president, not the second. I feel terrible that this mistake made it into the newsletter, for which I apologize.

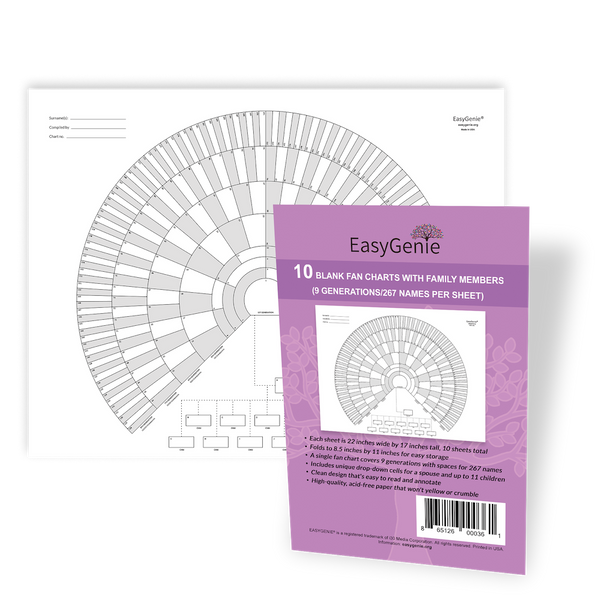

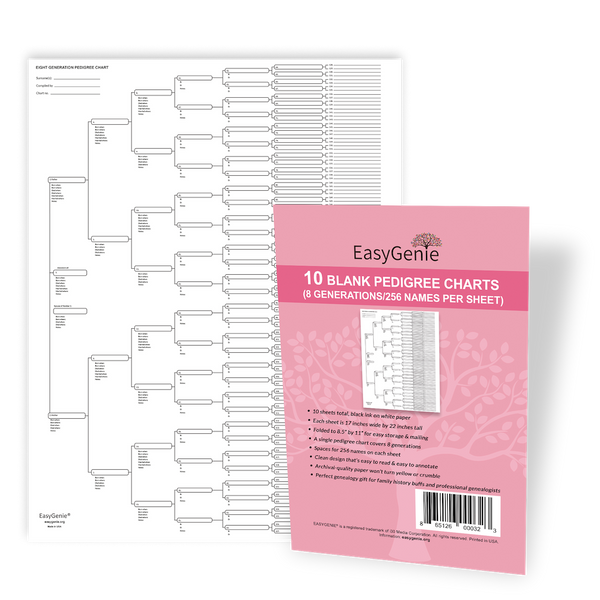

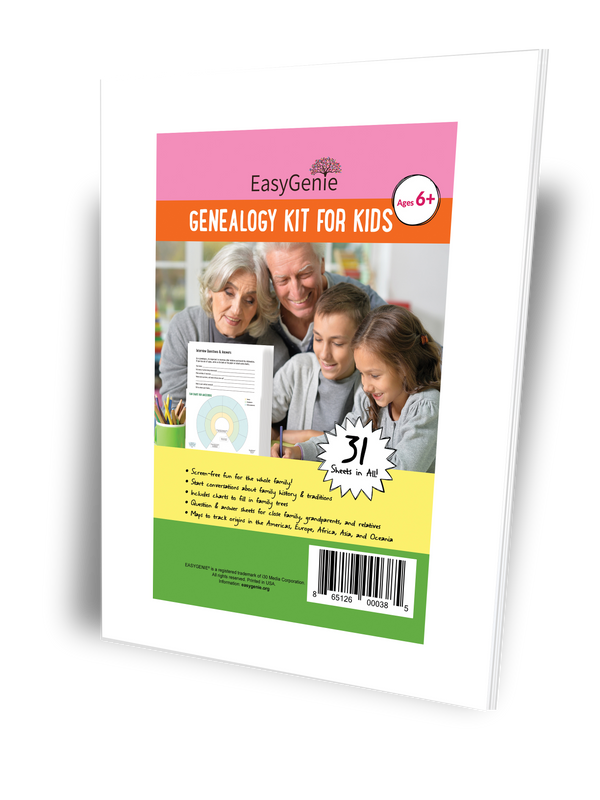

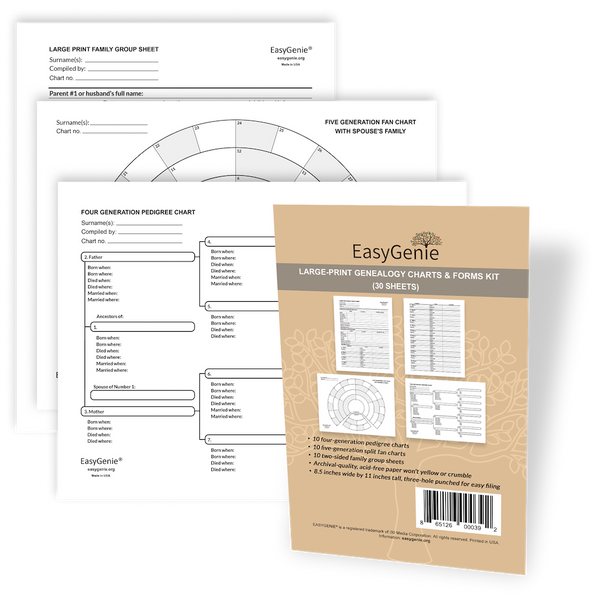

Unfortunately, it won’t be the last such error. EasyGenie is a small family-run business - it’s just Nicole and myself - and we can’t afford to hire a copy editor. I try my best to catch problems before they are published, but a few inevitably slip through.

Errors in Genealogy

Genealogists may understand where I am coming from. Building a family tree entails fact checking and validation of sources for hundreds or even thousands of people. Documents may leave out important details, or may be hard to read, such as the sample from an 1851 will shown below. Errors in genealogy are inevitable.

Some errors we may know about, or suspect. Things just don't add up. For instance, the 1880 census lists an ancestor’s parents as being born in England, even though a 1923 newspaper article said she grew up speaking Greek at home. And how could great uncle Daniel be a World War II vet if his birth certificate states he was born in 1930?

Fortunately, the path to the truth is usually straightforward: Dig into the research, and locate better historical sources or documentation, such as original wills or deeds from FamilySearch's full text search. Make sure that any family information shared online includes relevant sources, and refrain from adding people to your tree from other people’s poorly sourced FamilySearch, WikiTree, or Ancestry trees.

What about family stories? They can be difficult to verify, yet are so important to bringing ancestor’s experiences to life.

The key is to document and list those family stories that do exist (such as an interview with an older family member) and acknowledge when the story is not verified, or is mere hearsay (see Genealogy reality check: When it comes to famous ancestors, research is required).

Keep in mind that even though additional documentation may not exist now, it’s possible for new sources to bring clarity in the future. Such sources could include DNA test results, a new set of public records posted online, or a distant cousin who has better evidence that a particular tale was true.