Why we don't trust FamilySearch's unified family tree

Ian LamontSometimes, we use FamilySearch to see what other people (including distant cousins) have found and appended to FamilySearch's "unified family tree." Think of it as a master tree for all of humanity. The concept, as explained by FamilySearch, has merit:

"The FamilySearch shared tree strives to have just one public profile for every deceased person who has ever lived. Descendants contribute what they know about a person to a single, shared profile, rather than scattering their knowledge across multiple profiles on several trees, some of which may have privacy barriers."

It sounds like a great idea. However, the devil is, as the saying goes, in the details. And it's the details where the unified tree comes up short.

The quality of the contributions is inconsistent. Some of the research and information is solid. But a lot of the data is incorrect. Mistakes have been introduced to the tree, and made worse by a lack of verification. It's likely enthusiastic researchers who don't check the data may spread the mistakes far and wide on Ancestry and other unified trees like WikiTree ("where genealogists collaborate").

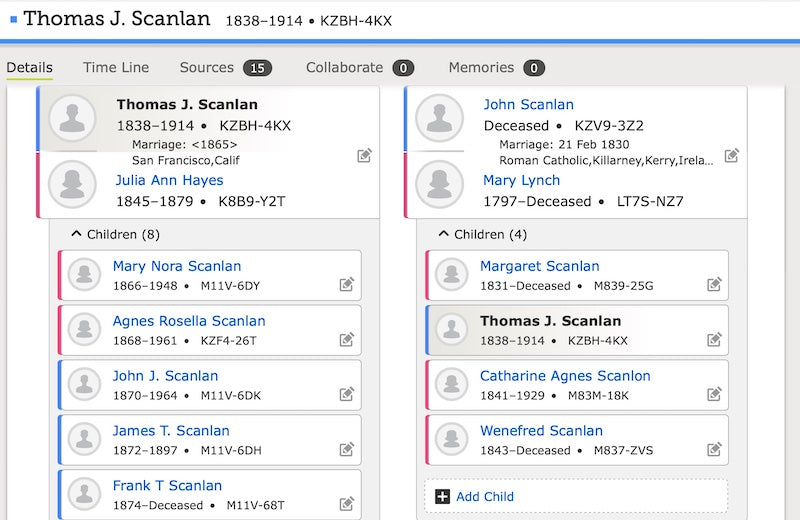

Take Thomas Scanlan/Scanlon. Tom is the brother of a maternal ancestor, Ian's great-great grandmother. We knew a lot about Tom's family, including his parents and siblings' names, his move to the Idaho frontier in the late 1800s, and the identities and occupations of his wife and children. Much of this information came from a detailed written history prepared by a great aunt nearly 50 years ago, who knew some of the elderly Scanlon siblings when she was a child.

But we did not know the place of origin in Ireland. Imagine our joy when we found Tom on the FamilySearch unified tree, with his wife Julia and kids in Idaho, and a place of origin - Askeaton, County Limerick, Ireland! The brick wall had been breached!

But something was off. Tom's mother's first and last name on the FamilySearch unified tree didn't match the name of the mother listed on his sister's death certificate. And on FamilySearch, a census showed the family living in Boston in 1860, a detail our great-aunt had never shared.

Who was Wenefred?

There were other problems. Only three of Tom's sisters were shown in the tree, who we had never heard of - Wenefred, Margaret, and Catherine. There was no sign of Tom's sister Mary, our great-great grandmother!

And how come the FamilySearch tree did not show any of the other brothers mentioned in our great aunt's written history? They included Patrick who ended up Seattle, and Michael, a ‘49er “who went to California in the Gold Rush and was never heard of again.” Emigrants joining the flow of pioneers headed West was an important part of our family's story, but the FamilySearch tree did not include these two men.

As for Askeaton, County Limerick, there was no source listed for this piece of information. Someone had appended it to Thomas' online record, without stating if it came from a death certificate, birth record, naturalization documents, or somewhere else.

Clearly, the FamilySearch tree had problems. We could see several other family historians had contributed to Thomas' FamilySearch entry, but we didn't recognize any of their handles or surnames. We considered the possibilities:

- Maybe Tom and Mary's father had remarried, which would explain two mothers. But the presence of just one on the unified FamilySearch tree would suggest that neither group of siblings were aware of the others ... except, perhaps, Tom and his father.

- In addition, the two groups of siblings had overlapping ranges of birthdates. That would suggest secret families or bigamy, both highly unlikely scenarios for pre-Famine Catholic Ireland.

It dawned on us that what had probably happened was another FamilySearch user - or even several users - had attached the wrong records to our family's Thomas Scanlon. It's a common name, after all. Maybe it was the Boston census record, identifying Wenefred and her two sisters.

With that one incorrect connection, other records were dug up to support this false assumption. The FamilySearch tree was clearly compromised.

Could we do anything to untangle the mess, and correct the mistakes? It would take hours of sleuthing and reaching out to the other contributors, with no guarantee of response or a satisfactory response or resolution.

Further, one of the most important aspects of genealogy is preserving stories of ancestors. Was it even possible to upload our great-aunt's written family history to FamilySearch, and cite it as a reliable record? Would anyone believe it?

In the end, we gave up using the information from the FamilySearch unified tree. While we want to establish facts, share important resources and help others understand our shared ancestry, we don't have the time to deal with a big mess created by other people that may never be cleaned up.

But this experience reinforced a very important lesson: Be very careful with the information found on online trees, whether they are FamilySearch's unified tree or personal trees shared on Ancestry. Sometimes they provide answers, but often they lead family genealogists down the wrong path.